Comparison of Permanent Magnet Materials: Properties, Performance, and Applications

Permanent magnets are important because they furnish stable magnetic fields conveniently. In many instances, modern magnets furnish higher magnetic fields than electromagnets. For example, in some small motors they not only eliminate wire wound electromagnets, which require direct current to be energized, but also may use less space. The new rare earth permanent magnets will expand and modify technological applications in this field. With this in mind, we present a brief survey of some of the older materials, a comparison with the new materials, and a listing of their applications.

There are numerous applications for permanent magnets, each of which requires consideration of many factors. For this reason, a large number of magnets having different magnetic

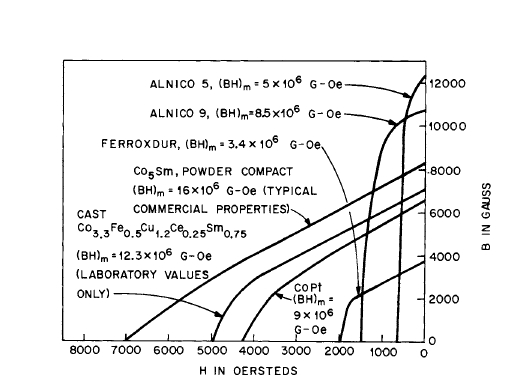

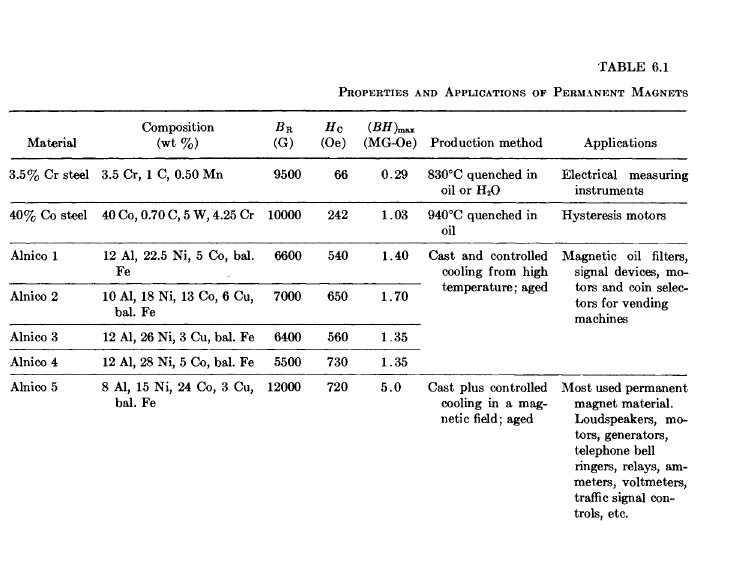

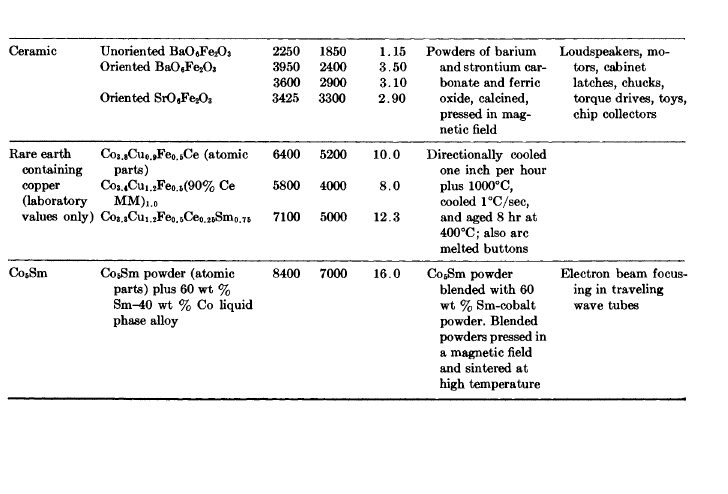

and physical properties are manufactured. Figure 6.1 shows a comparison of \((BH)_{m}\) and the second - quadrant hysteresis loop for some of the older alloys and the new permanent magnet materials. In general, the latter have higher values of coercivity and maximum energy products. The older materials are relatively cheaper because of lower raw materials and processing costs; but in time, with new designs and applications, the new rare earth permanent magnets will find increased use. The properties and applications of some of the older and newer materials are given in the following discussion and in Table 6.1.

Figure 6.1 Comparison of the typical properties of some of the older permanent magnet materials with those based on \(\text{Co}_{5}\text{R}\) compounds.

Martensitic Magnet Steels: Strength, Durability, and Magnetic Properties

Materials of this type were practically the only ones used before 1930. In general, there are two classes: the high - carbon steels and the cobalt - steel magnets. The former exhibit coercive forces up to 70 Oe and the latter from 70 to 250 Oe. The high - carbon steels are cheap and are used for compasses, ammeters, and voltmeters. The cobalt steels are sometimes used for hysteresis motors. Because of the martensitic nature of the phase change occurring near room temperature, all magnet steels have to be aged above the temperature at which they are to be used in order to stabilize the structure. With the advent of the precipitation hardened magnets, the use of magnet steels has been limited.

Alnico Magnets: Composition, Characteristics, and Industrial Uses

These alloys, invented by Mishima in 1932, have been greatly modified and improved during the past forty years by the continuous work of many researchers [1 - 15]. They are the most useful of permanent magnet alloys. Maximum energy products vary from approximately 1 to \(9\times10^{6}\text{ G - Oe}\), coercive forces range from 400 to 2000 Oe, and residual inductions range from 5000 to 13,000 G. The alloys are hard and brittle, and they are usually cast and ground to shape. Small parts are sometimes made by powder metallurgy techniques.

Alnico 1, 2, 3, and 4 represent the earlier developments of the alloys. They are sometimes used for magnetos, motors, and coin selectors for vending machines.

Alnico 5 is the most widely used. By cooling this alloy in a magnetic field, its energy product is increased threefold. The response to magnetic annealing was a major advance in Alnico research. Although for most Alnicos \(1300^{\circ}\text{C}\) is a good solution temperature, it is not always necessary heat to this high temperature for magnetic annealing if the casting is cooled sufficiently fast from the melt. It can be reheated to approximately \(900^{\circ}\text{C}\) and cooled in a field. The magnetic properties of this alloy can be achieved in straight or curved sections. When the crystal structure is oriented (directional grain), the energy product is further enhanced; but orientation can be achieved with ease only in straight sections, and its cost is greater. Materials of this type are used for loud - speakers, motors, generators, vending machines, and tele - phone receivers.

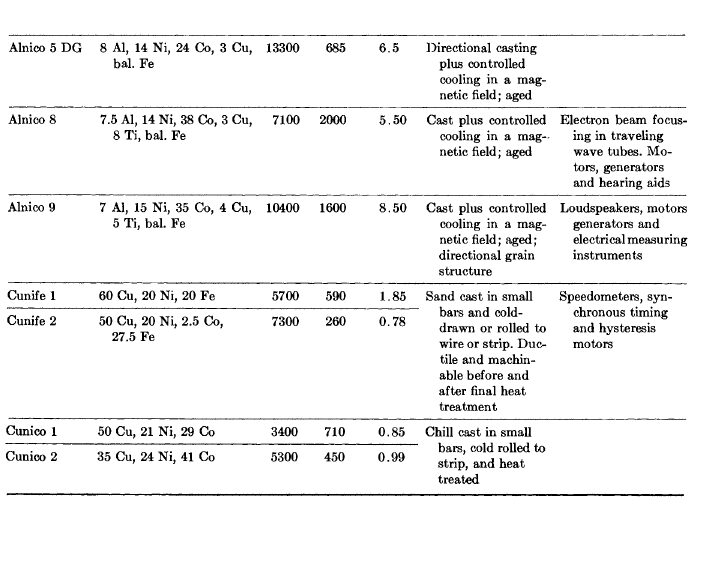

Alnico 8 combines high coercive force and high energy product. It is used in applications where high coercive force is necessary, such as electron beam focusing in traveling wave tubes, motors, generators, and hearing aids.

Alnico 9 combines high coercive force with the highest energy product of the Alnicos. It has an oriented crystal structure. Applications include loudspeakers, motors, generators, and measuring instruments.

Cunife and Cunico Magnets: Understanding Their Unique Magnetic Behavior

Cunife I alloy [16] consists of 20% Ni, 20% Fe, and 60% Cu (wt %). An important feature of this alloy is that it can be cold worked at room temperature and therefore can be made into thin strip and wire. It can be sheared, punched, and machined. The material is used for hysteresis and synchronous timing motors, compasses, and speedometers. Cunico I alloy [17] consists of 50% Cu, 21% Ni, and 29% Co. It can also be rolled into thin strip and cast into complex shapes.

Remalloy: Properties and Applications of This Magnetic Alloy

Two Remalloy compositions [18] are of interest, 17% Mo, 12% Co, 71% Fe and 20% Mo, 12% Co, 68% Fe (wt %). Ingots of these materials are usually hot rolled to bars and strips. They are used primarily in telephone receivers. For this application, it is necessary that the materials also exhibit mechanical properties that permit hot forging into a cuplike shape.

Vicalloys: Exploring the Magnetic Capabilities of Cobalt-Iron Alloys

The Vicalloys [19] initially covered a composition range of 30 - 52% Fe, 36 - 62% Co, and 4 - 16% V. Later [20], investigations extended the range to include compositions from the nominal 4% V down to 0.25% V. Applications of Vicalloys [21] result principally from the fact that they can be cast into large billets and rolled into thin sheets. One commercial application required 1000 - ft lengths 4 - in. wide × 0.001 - in. thick. The alloys are used in memory systems, relays, clock and hysteresis motors, clutches, and focusing rings for television picture tubes.

Platinum-Cobalt Magnets: High-Performance Alloys for Advanced Applications

This alloy, nominally 23.3 wt % Co and 76.7 wt % Pt, exhibited the highest coercive force [22, 23] that was obtained prior to the advent of the rare earth permanent magnet alloys. The alloy, which undergoes an order - disorder reaction, must be heat treated to realize this high coercivity [24]. Because platinum is costly, its use is restricted. Applications presently include magnets for electron beam focusing in traveling wave tubes and in motors for electric wrist watches.

γ-Fe₂O₃ and Fe₃O₄: Magnetic Oxides and Their Technological Significance

Recording tape is made by uniformly coating paper or plastic with \(\gamma\text{Fe}_{2}\text{O}_{3}\) or \(\text{Fe}_{3}\text{O}_{4}\) particles that are approximately 0.5 - 1.0 \(\mu\text{m}\) in diameter. Coercive force values range from 200 to 600 Oe and residual inductions from 600 to 1000 G. This application represents the largest dollar volume in the permanent magnet industry.

Hexagonal Ferrite (Ceramic) Magnets: Structure, Benefits, and Usess

This class of materials [25, 26] is commercially important for a number of reasons. The raw materials are inexpensive (iron oxide and barium or strontium carbonate powders), and the magnets possess high coercive force (1850 - 3300 Oe) with reasonable values of residual induction (2250 - 3950 G).

The demagnetization curves approach a straight line. Usually these magnets are used in short lengths with large cross - sectional areas.

In general, there are three classes of this material. First is the nonoriented \(\text{BaO}\cdot6\text{Fe}_{2}\text{O}_{3}\) magnet. Such magnets are used for torque drives, small motors, cabinet latches, and toys. The second class is material in which the grains are oriented by pressing the powder in a magnetic field. This material has a higher maximum energy product and is used for loudspeakers, motors, magnetic separators, and torque drives. Sometimes there are several variations of this grade, depending on whether high flux or high coercive force is desired. The third class, oriented \(\text{SrO}\cdot6\text{Fe}_{2}\text{O}_{3}\), is sometimes used because the material exhibits a high coercive force of 3300 Oe.

Ceramic magnets have several disadvantages in comparison with the Alnicos. Their maximum energy products are low, and temperature coefficients are greater than that of Alnico 5.

Rare Earth Magnets: The Strongest Permanent Magnets and Their Innovations

In the decade 1960 - 1970, a significant advance was made in permanent magnet materials as a result of the technological exploitation of the magnetic properties of \(\text{Co}_{5}\text{R}\) compounds via castable alloys or by powder metallurgy techniques. As discussed in this monograph, castable permanent magnet alloys are obtained when some of the cobalt is replaced with copper. An outstanding feature of these cast alloys is their high value of intrinsic coercive force in comparison with the older permanent magnets. Also, the material containing copper can utilize to good advantage the cheapest of the rare earth elements, cerium or 90% Ce misch metal.

The \(\text{Co}_{5}\text{R}\) compounds, with or without copper additions, can be made into magnets by powder metallurgy techniques. As discussed in Chapter V, this process consists of grinding the alloy into a fine powder and pressing the powder in a strong magnetic field to orient the particles. Usually, the material is sintered after pressing. Powders of the compounds made without copper have to be more finely ground, but their energy products are higher. Presently, permanent magnets of these materials are being used for electron beam focusing in traveling wave tubes and are replacing the \(\text{Co}-\text{Pt}\) magnets. In time, new designs and applications will increase the usefulness of these materials.