Co₅R Permanent Magnets Based on Powders: Properties and Applications

The powder metallurgy technique is an excellent approach to the production of small and/or intricately shaped magnets. As a starting point, Co5R ingots are prepared by standard melting techniques and ground to powder by a number of methods. These methods include ball milling, attritor, and vibratory milling. Because these materials oxidize readily when in fine powder form, care must be taken during grinding to prevent oxidation. Grinding is done in an inert gaseous atmosphere, or in a protective organic liquid, such as toluene or isopropyl alcohol. In this chapter, the properties of the powders, methods of producing magnets, and properties of magnets are described.

Magnetic Behavior of Powders: Understanding Their Role in Permanent Magnets

The theory of the magnetic behavior of fine particles [1 - 3], formulated to account for the high coercivities of alloys of the Alnico type and fine grains of permanent - magnet materials, suggested that magnetic particles below a critical size can be single domain. Domain wall processes are then absent, and the coercive force is determined by coherent domain rotation of the magnetization vector against anisotropy forces. This stimulated much research and development in subsequent years on fine - particle permanent - magnet materials, and with this in mind, it was shown [4] that \(\text{Co}_{5}\text{Gd}\) in the form of \(- 100+200\) mesh powder exhibited an intrinsic coercivity of 8000 Oe. Subsequent studies of \(\text{Co}_{5}\text{Sm}\) (\(<10\ \mu\text{m}\)) yielded intrinsic coercivities (\(_{M}H_{c}\)) in excess of 9000 Oe and 13,000 Oe, and powders compressed in a field of 7000 Oe with various binders yielded small laboratory magnets of \((BH)_{max}=5.1 - 8.1\times10^{6}\text{ G - Oe}\) [5, 6]. Even though the packing densities were low, these values are far less than those theoretically expected for these materials, which have very large magnetocrystalline anisotropy.

It was found that:

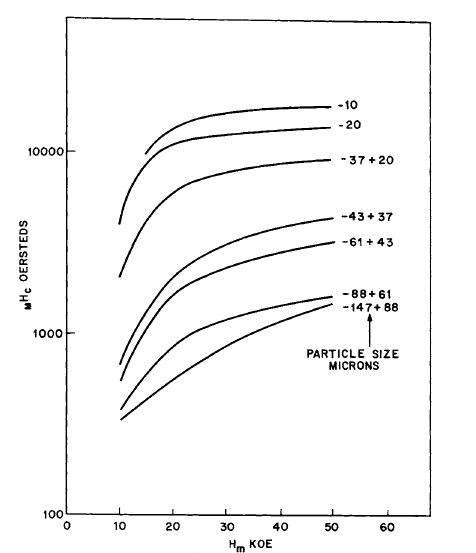

- \(_{M}H_{c}\) of the powders exhibited an unusually large dependence of the magnitude of the magnetic field \(H_{m}\) applied before the coercive - force measurements. Note the almost linear relationship between \(_{M}H_{c}\) and \(H_{m}\) for particle size \(( - 147+88)\) of Figure 5.1.

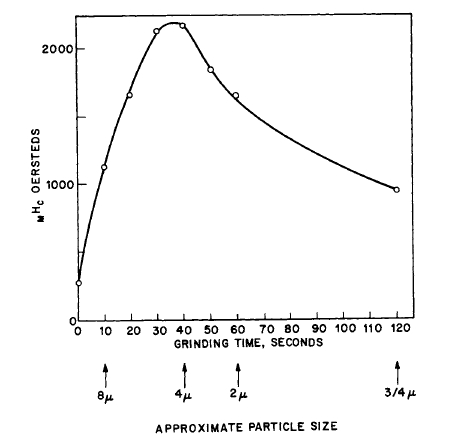

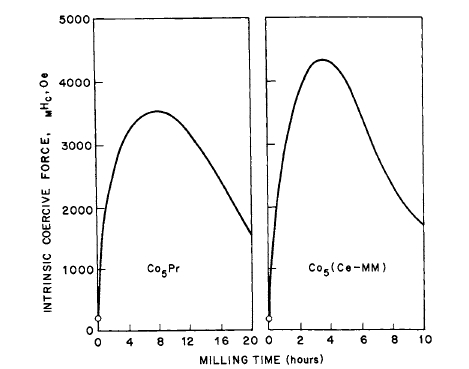

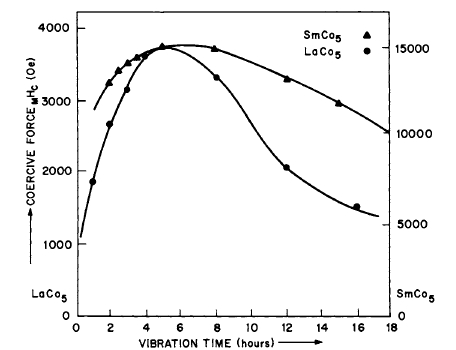

- \(_{M}H_{c}\) was particle - size dependent, i.e., increased with grinding time, in some cases reaching a maximum, then decreasing after prolonged milling* (Figures 5.2 - 5.5) [6, 9 - 14].

* Similar behavior has been observed for \((\text{Fe},\text{Co})_{2}\text{P}\) and

Figure 5.1 Variation of the intrinsic coercive force of \(\text{Co}_{5}\text{Sm}\) powders as a function of magnetizing field \(H_{m}\) (after Becker [7]).

MnAlGe as well as for other materials [8, 9]. Annealing may or may not remove the effect of prolonged milling.

Figure 5.2 Variation of the intrinsic coercive force of \(\text{Co}_{5}\text{Y}\) with grinding time (and particle size) in a high - speed vibratory mill (after Becker [7]).

c. Remanent magnetization and loop squareness increased with increasing applied field [7, 14].

d. There was angular variation of coercive force. Difficulty in magnetically aligning the particles is also encountered at the micron sizes [7, 14].

As first pointed out by Brown [15], if magnetic particles were perfectly uniform ellipsoids, the coercive force should be equal to the anisotropy field \(H_{A}\) and independent of particle size.

Figure 5.3 Effect of milling time on intrinsic coercive force of \(\text{Co}_{5}\text{Pr}\) and \(\text{Co}_{5}(\text{Ce - MM})\) (after Strnat [10]).

ticle size. The low observed coercivities of fine particles compared to the theoretical estimates expected in materials in which magnetocrystalline anisotropy dominates, and the marked dependence of coercivity on particle size, have been referred to as “Brown's Paradox.” It was suggested that these low coercivities are due to crystal imperfections [15 - 19]. For the \(\text{Co}_{5}\text{R}\) powders, it was suggested that domain nucleation and domain wall motion processes are important in fine powders and that nucleation of reverse domains can occur at much lower fields because of lattice defects (x - ray line broadening is observed after grinding) and surface irregularities, such as sharp edges, fine cracks, pits, and surface oxides [16, 20].

Figure 5.4 Variation of intrinsic coercive force as a function of vibration time in a vibratory mill (after Velge and Buschow [6]).

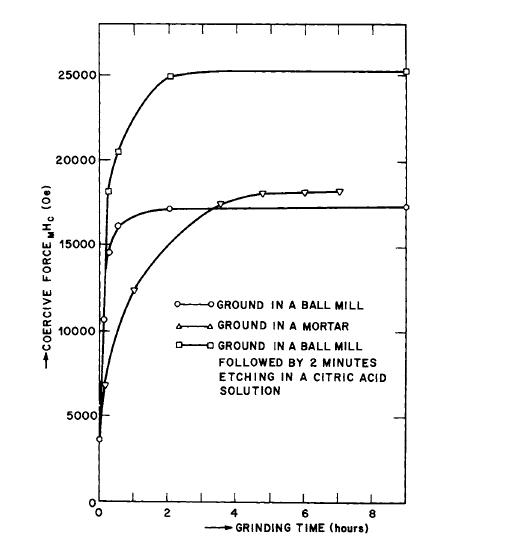

In an excellent study of polished and unpolished single particles of \(\text{Co}_{5}\text{R}\), Becker [21, 22] has directly verified that fine particles of these materials can be treated in a manner in which no large - scale magnetization rotation takes place and that their properties are determined by nucleation and domain boundary motion [23]. Figure 5.5 illustrates the effect of removing the damaged layer on \(\text{SmCo}_{5}\) particles. Discontinuous magnetization changes were observed and occurred at reproducible fields, the values of which depended on the value of the previously applied field used to saturate the sample. It is suggested that domain boundaries are not always driven out of the material and that the strong dependence of coercive force on applied field is associated with nucleation

Figure 5.5 Effect of removing the damaged layer on the intrinsic coercive force of \(\text{Co}_{5}\text{Sm}\) powders (after Buschow et al. [13]).

and unpinning of domain boundaries. If all the domain walls are driven out of the material, a greater reverse field will be required to nucleate a domain. The probability that a particle contains a defect of a given severity decreases with

decreasing particle size, accounting for the initial increase in coercivity with decreasing particle size. Thus, his model explains the strong variation of coercive field and smaller variation of remanence with magnetizing field and particle size, as well as the angular variation of coercive force and behavior of rotational hysteresis [14, 21].

Zijlstra's analysis and model [24] of domain wall processes in \(\text{Co}_{5}\text{Sm}\) powders confirm the fact that wall motion is the predominant magnetization process, but emphasizes the role of wall pinning in determining the coercivity [24, 25]. In a study of hysteresis loops of single particles of \(\text{Co}_{5}\text{Sm}\), \(\text{Co}_{5}\text{Pr}\), and \(\text{Co}_{5}\text{La}\) Zijlstra [26] has shown evidence for wall pinning both near the surface and in the interior of the fine particles. Aging at \(100^{\circ}\text{C}\) promotes nucleation, but affects the pinning behavior to the extent that the wall - pinning model is valid. The coercivity of electrolytically etched particle of \(\text{Co}_{5}\text{Sm}\) seems to be determined by nucleation of domain walls [25]. The wall - pinning model is also applicable to \(\text{Co}_{5}\text{Pr}\) and to \(\text{Co}_{5}\text{La}\) [25]. The nature of the pinning sites is not known.

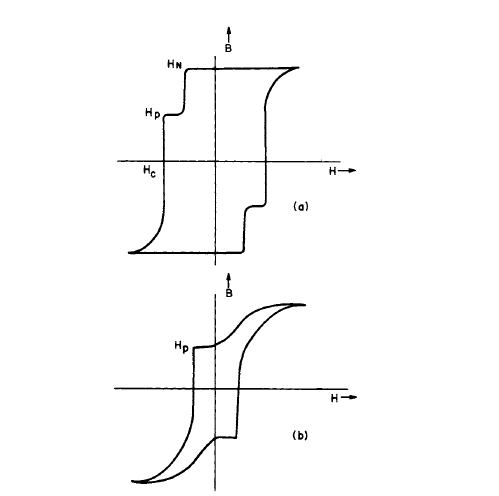

Figure 5.6 schematically illustrates two similar to those obtained experimentally in magnetizing and demagnetizing single particles of the \(\text{Co}_{5}\text{R}\) phases. In Figure 5.6a, after magnetization there are no domain walls present and nucleation finally occurs at the field \(H_{n}\). An additional jump in flux occurs at \(H_{p}\), where the wall is unpinned. In Figure 5.6b, after magnetization a domain wall remains and the flux decreases in a curved manner until a flux jump occurs at the pinning site \(H_{p}\).

The difference in magnetic behavior of ground particles of \(\text{Co}_{5}\text{Y}\), \(\text{Co}_{5}\text{Pr}\), \(\text{Co}_{5}(\text{Ce - MM})\), and \(\text{Co}_{5}\text{La}\), compared to the behavior of \(\text{Co}_{5}\text{Sm}\), has been suggested as possibly due to a difference in mechanical behavior [7]. \(\text{Co}_{5}\text{Sm}\) may be more brittle and less subject to plastic deformation at the particle

Figure 5.6 Illustration of two of the many possible hysteresis loops exhibited by single particles of \(\text{Co}_{5}\text{R}\) materials. In (a), the coercivity is determined by nucleation and pinning of the domain wall. In (b), the coercivity is determined mainly by pinning of the domain wall.

surface. It was further suggested that the difference in mechanical behaviors might be associated with differences in lattice parameter [27] and in gas content (\(O_{2}\) and \(H_{2}\)) [22].

The importance of the nature of the particle surface is apparent. These materials oxidize readily (spontaneously in air

when in fine powder form). By properly protecting the \(\text{Co}_{5}\text{R}\) compounds during grinding, magnetically aligning the individual particles, pressing, and sintering to relative densities in excess of 95%, \(\text{Co}_{5}\text{R}\) powder magnets have been produced with \((BH)_{max}\) in excess of \(20\times10^{6}\text{ G - Oe}\).

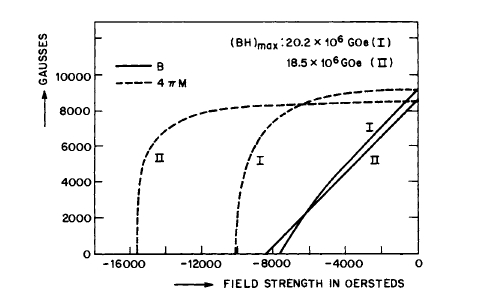

Methods of Producing Co₅R Permanent Magnets and Their Key Properties

The technique of Buschow et al. [13] is a cold - pressing technique which consists of arc or induction melting of the \(\text{Co}_{5}\text{Sm}\) compound in ceramic crucibles, grinding to powder, stabilizing the powder against oxidation by electroless plating of Ni in an acid bath, orienting the powder in an applied field at 30 kOe under moderate pressure, and then packing in a rubber container and hydrostatically compacting (20 kbar) to an average density of 82%. Further pressure increments only increased the density slightly. The compact is then packed in lead foil wetted with mercury and subjected to moderate oil pressure for 10 hr. The \(\text{Pb - Hg}\) alloy which forms totally encloses the specimen, which is then subjected to a uniaxial hydrostatic (20 kbar) deformation which results in a compaction density of 97%. The degree of orientation of the powder particles is not affected by this treatment, and a magnet produced this way exhibited a \((BH)_{max}\) of 18.5 MG - Oe. By increasing the cobalt content of the starting material, the saturation and remanence are increased so that \((BH)_{max}\) is raised to 20.2 MG - Oe. However, \(_{M}H_{c}\) is lowered drastically. For \(\text{Co}_{5}\text{Sm}\) (same crystal structure), \(_{M}H_{c}\) decreases by 40%. There is a homogeneity range for \(\text{Co}_{5}\text{Sm}\) at the elevated temperatures.

The Ni plating results in an increase in \(_{M}H_{c}\) from 11,000 to 22,000 Oe, but this may be due to an etching effect during

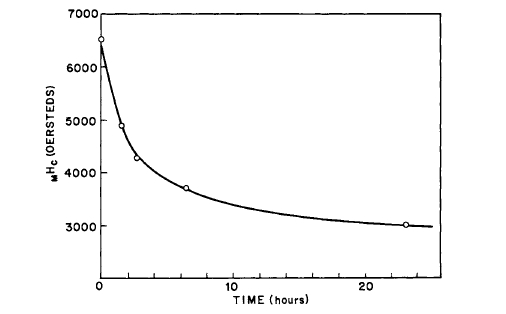

plating (see Figure 5.5, for example). The magnetization - temperature curve for \(\text{Co}_{5}\text{Sm}\) powder so produced is shown in Figure 5.7 [13]. Demagnetization curves for two magnets are shown in Figure 5.8. The first (Composition II) was made by using low - Co content \(\text{Co}_{5}\text{Sm}\) (\(\text{Co}:\text{Sm}=5:1\)) and prolonged milling followed by etching, while the second (composition I) was pressed from powder with high Co content, ground for a relatively short time. The magnets appear to be subject to a slow decrease in coercivity with time (\(_{M}H_{c}\) decreases 10 - 20% after four weeks and then stabilizes), but this change does not affect the \(B\) vs. \(H\) demagnetizing curve for all intents and purposes if \(_{M}H_{c}\) is high enough initially.

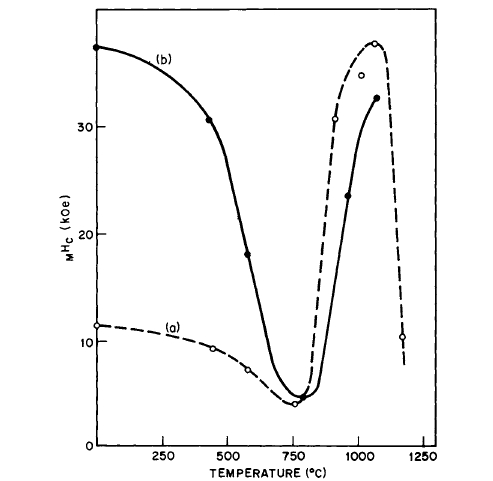

The coercivity of \(\text{Co}_{5}\text{Sm}\) compacts is sensitive to annealing temperature [13, 28]. The coercivity decreases up to temperatures of \(\sim800^{\circ}\text{C}\), but increases again after heating to higher temperatures; \(_{M}H_{c}\) values as high as 43,000 Oe were observed (Figure 5.9). Extreme precautions to exclude air

Figure 5.7 Magnetization of \(\text{Co}_{5}\text{Sm}\) powder used for cold - pressed magnets as a function of temperature in a field of 5450 Oe (after Buschow et al. [13]).

Figure 5.8 Demagnetization curves for two Sm - Co magnets (after Buschow et al. [13]). Composition I has a high cobalt content (\(\text{Co}_{5}\text{Sm}\)), which yields high \((BH)_{m}\) and low \(_{M}H_{c}\). Composition II is for \(\text{Co}_{5}\text{Sm}\).

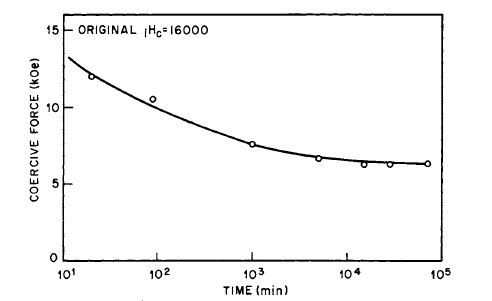

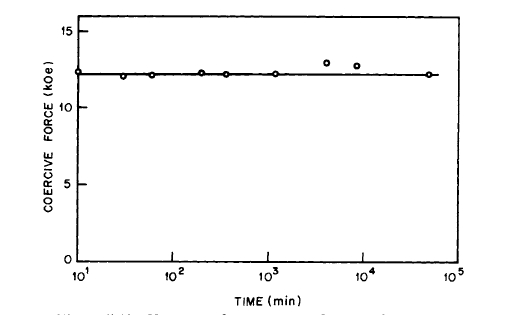

did not prevent the formation of as much as 2% \(\text{Sm}_{2}\text{O}_{3}\) in the heated samples. The behavior of \(\text{Co}_{5}\text{Sm}\) magnets on annealing is explained on a wall pinning model rather than on a nucleation model [28]. Subsequently, it was shown that the aging of cold - pressed \(\text{Co}_{5}\text{Sm}\) magnets is due to reaction with adsorbed air and \(H_{2}O\) vapor. By preparing the powders in oxygen - free atmospheres, such as argon, nonaging cold - pressed magnets can be prepared [29]. The effect of heating \(\text{Co}_{5}\text{Sm}\) powder in air is illustrated in Figure 5.10 [7]. The effect of heating cold - pressed magnets prepared in air and argon is shown in Figures 5.11 and 5.12. It is now suggested that the behavior of \(\text{Co}_{5}\text{Sm}\) compacts as shown on Figure 5.9 is due to the eutectoid decomposition of \(\text{Co}_{5}\text{Sm}\) which occurs at \(\sim750^{\circ}\text{C}\) [46].

The process of Das [30] consists of grinding \(\text{Co}_{5}\text{Sm}\) ingots

Figure 5.9 Intrinsic coercivity of pressed powder samples measured at room temperature after heating for 30 min at the indicated temperatures. Curve (a), as - ground material. Curve (b), ground material heated at \(1080^{\circ}\text{C}\) and heated the second time at the indicated temperature (after Westendorp [28, 29]).

to below 25 \(\mu\text{m}\), coating the particles with tin by electroless plating, orienting in a magnetic field, and pressing at \(\sim6.7\) kbar. Cold welding of the tin coating occurs at this stage. The density is approximately 70% and the degree of alignment of

Figure 5.10 The effect of heating in air for various times at \(115^{\circ}\text{C}\) on the intrinsic coercive force of aligned \(-325\) mesh \(\text{Co}_{5}\text{Sm}\) powder (after Becker [7]).

the particles 80%. Sintering in an inert atmosphere at approximately \(1100^{\circ}\text{C}\) for 1 hr results in magnets of nearly 100% theoretical density having \((BH)_{max}=16 - 20\text{ MG - Oe}\). Subsequently, Das has described a different process which is equivalent to liquid phase sintering described below because his average composition is in a two - phase region in the Co - Sm phase diagram (Chapter II).

The technique referred to as liquid phase sintering has been employed to consolidate \(\text{Co}_{5}\text{Sm}\) powders to yield permanent magnets having \((BH)_{max}\) in excess of 15\text{ MG - Oe}\) [31 - 33]. \(_{M}H_{c}\) values as high as 30,000 Oe were reported [22]. Long time exposure to air at \(150^{\circ}\text{C}\) did not degrade the samples, and the loss of coercive force of stoichiometric \(\text{Co}_{5}\text{Sm}\), which occurs on heating to approximately \(1100^{\circ}\text{C}\), did not occur by use of this technique [31]. It consists of grinding stoichiometric

Figure 5.11 The variation of coercive force with time of aging at \(100^{\circ}\text{C}\) for a cold - pressed \(\text{Co}_{5}\text{Sm}\) magnet prepared in air (after Westendorp [29]).

\(\text{Co}_{5}\text{Sm}\) to 6 - 8 \(\mu\text{m}\) by means of a fluid energy mill using \(N_{2}\) as the working gas, blending into it a powder of a Sm - rich alloy (40 wt % Co, 60 wt % Sm), so that the powder has an average composition of \(\sim63\) wt % \(\text{Co}_{5}\text{Sm}\). The powder is placed in rubber tubes, aligned in a field of 60 - 100 kOe, evacuated, and hydrostatically pressed at 13.8 kbar. Sintering is subsequently carried out at \(1100^{\circ}\text{C}\) in high purity argon for 1/2 hr. The Sm - rich alloy blended into stoichiometric \(\text{Co}_{5}\text{Sm}\) yields a liquid phase at this temperature. Since stoichiometric \(\text{Co}_{5}\text{Sm}\) forms peritectically anyway, there probably is insufficient liquid phase present under ordinary sintering conditions to take part in the etching of the particles and subsequent densification. Excess Sm can also act as an oxygen scavenger.

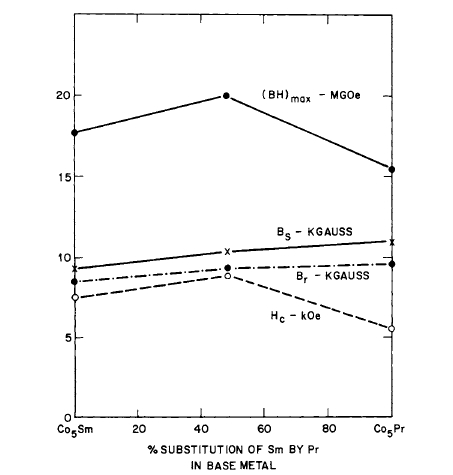

The liquid phase sintering technique has been applied also to a series of ternary \(\text{Co}-\text{R}\) alloys using Sm, Pr, La, Ce, and

Figure 5.12 Variation of coercivity with time of aging in air at \(150^{\circ}\text{C}\) for a cold - pressed \(\text{Co}_{5}\text{Sm}\) magnet prepared in argon (after Westendorp [29]).

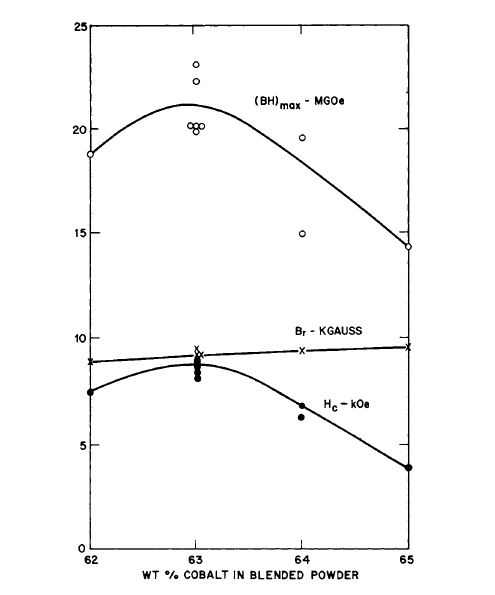

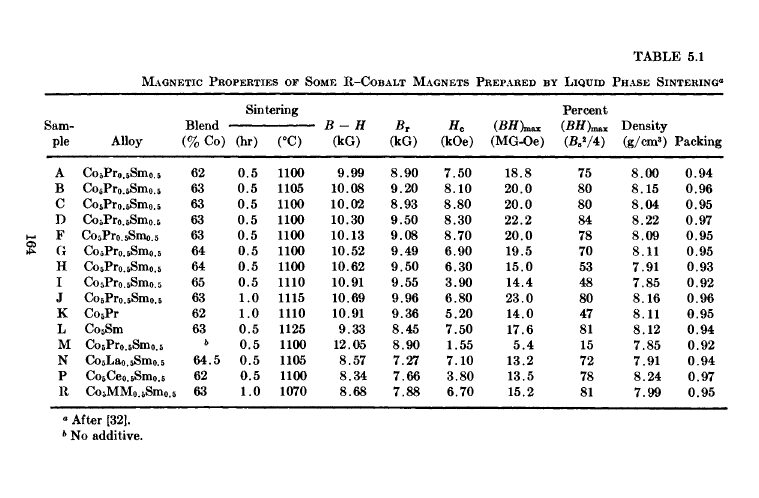

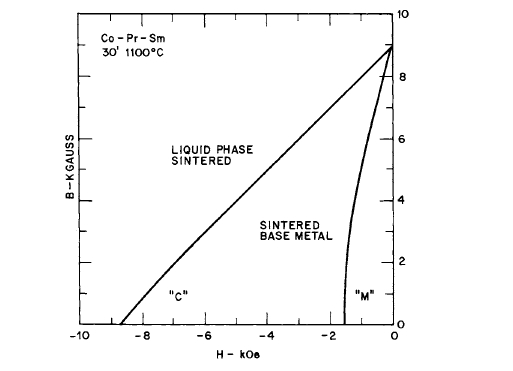

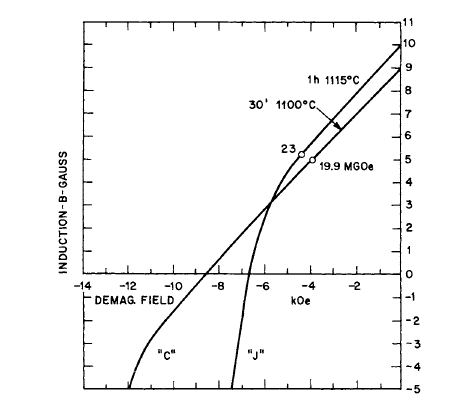

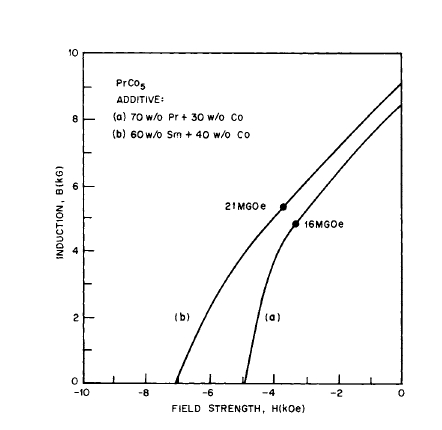

MM (misch metal) [32]. Stable high energy product magnets were made; the alloy \(\text{Co}_{5}\text{Pr}_{0.5}\text{Sm}_{0.5}\) gave \((BH)_{max}=23\text{ MG - Oe}\), while the alloys \(\text{Co}_{5}\text{Ce}_{0.5}\text{Sm}_{0.5}\) and \(\text{Co}_{5}\text{MM}_{0.5}\text{Sm}_{0.5}\) yielded \((BH)_{max}\) of 13.5 and 15.2\text{ MG - Oe}\) respectively. The powder blend of all three materials consisted of 63, 62, and 63 wt % Co respectively. Since Sm is a rather expensive element, substitution of Ce and MM reduces the cost of magnets made with these materials. The effect of additive, as given by the total weight per cent of cobalt in the blend, on the magnetic properties of \(\text{Co}_{5}\text{Pr}_{0.5}\text{Sm}_{0.5}\) magnets made by liquid phase sintering is shown in Figure 5.13. (See also Table 5.1.) The demagnetization curves for a liquid phase sintered magnet compared with those for a magnet made from the same base metal (\(\text{Co}_{5}\text{Pr}_{0.5}\text{Sm}_{0.5}\)) by normal solid - state sintering are shown in Figure 5.14. The effect of thermal treatment on the

Figure 5.13 The effect of additive, as given by the total weight per cent of cobalt in the blend, on the magnetic properties of \(\text{Co}_{5}\text{Pr}_{0.5}\text{Sm}_{0.5}\) magnets made by liquid phase sintering (after Martin and Benz [32]).

Figure 5.14 Demagnetization curves for a liquid phase sintered magnet compared with a magnet made from the same base metal (\(\text{Co}_{5}\text{Pr}_{0.5}\text{Sm}_{0.5}\)) by normal solid - state sintering. The data for samples “C” and “M” are listed in Table 5.1 (after Martin and Benz [32]).

demagnetization properties of two Co - Pr - Sm magnets is shown in Figure 5.15. The effect of substitution of Pr for Sm in liquid phase sintered magnets and the recoil curves for a Co - La - Sm alloy magnet are shown in Figures 5.16 and 5.17 respectively.

Because \(\text{Co}_{5}\text{Pr}\) has the largest theoretical energy product, the liquid phase sintering technique was applied to \(\text{Co}_{5}\text{Pr}\) by the addition of Sm - Co and Pr - Co alloy additives as liquid phase sintering aids [34]. For a \(\text{Co}_{5}\text{Pr}\) magnet with a Sm - Co alloy addition, the following properties were obtained: \(B_{r}=\)

Figure 5.15 Effect of thermal treatment on demagnetization properties of two Co - Pr - Sm magnets of the same nominal composition (after Martin and Benz [32]).

9210 G, \(_{M}H_{c}=12,670\) Oe, \(_{B}H_{c}=7140\) Oe, \((BH)_{max}=21.1\text{ MG - Oe}\) (Figure 5.18). Liquid phase sintering has been used to prepare laboratory magnets of \((\text{Sm - MM})\text{Co}_{5}\) \((BH_{max}=20\text{ MG - Oe})\) [35] and \(\text{Pr}_{0.85}\text{Nd}_{0.15}\text{Co}_{5}\) \((BH_{max}=13\text{ MG - Oe})\) [36].

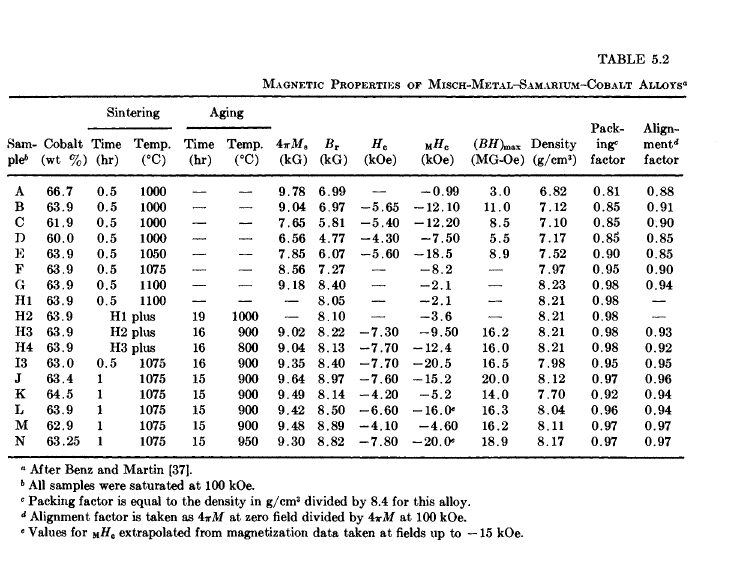

The processing and properties of \((\text{MM - Sm})\text{ - Co}\) magnets prepared by liquid phase sintering have been described in detail [37]. Powder of chill - cast ingots of composition 66 wt % Co, 17 wt % MM, 17 wt % Sm, and 40 wt % Co - 60 wt % Sm were blended together to give compositions of various total cobalt

Figure 5.16 Effect of substitution of Pr for Sm in magnets made by liquid phase sintering. The additive was Sm - 40 wt % Co (after Martin and Benz [32]).

contents. The results of the effect of composition, sintering time, and temperature, and of thermal aging after sintering, on the magnetic properties are shown in Table 5.2.

Intrinsic coercivities of ground powders (\(<20\ \mu\text{m}\)) of \(\text{Co}_{5}\text{MM}\) and \(\text{Co}_{5}\text{Pr}\) have been improved considerably by treat-

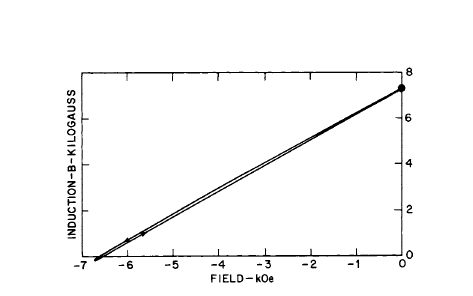

Figure 5.17 Recoil curve for a Co - La - Sm alloy magnet (after Martin and Benz [32]).

Figure 5.18 Demagnetization curves for liquid phase sintered \(\text{PrCo}_{5}\) magnets with two different sintering aids (after Tsui and Strnat [34]).

Figure 5.19 Effect of aging time on reduction of \(_{M}H_{c}\) for several \(<37\ \mu\text{m}\) Sm - Co based alloy powders. Aging was done in air at \(125^{\circ}\text{C}\). Magnetizing field, 22.4 kOe (after Strnat [41]).

Figure 5.20 Demagnetization curve of sintered \(\text{Co}_{0.8}\text{Cu}_{0.5}\text{Fe}_{0.6}\text{Ce}\) with an energy product \((BH)_{max}\) of 9.3\text{ MG - Oe}\) (after Sherwood et al. [42]).

ment in acid and heating to \(400^{\circ}\text{C}\) with 5% zinc dust [38]. However, the liquid phase sintering methods eliminate the necessity for this treatment.

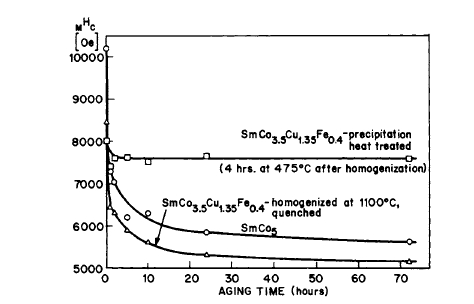

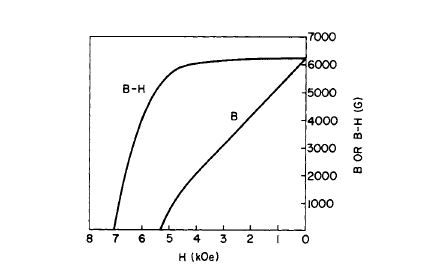

The use of coarse particles \((37 - 105\ \mu\text{m})\) of \(\text{Co}-\text{Cu}-\text{Fe}(\text{Cu},\text{Sm},\text{MM})\) for magnets via powder metallurgy techniques has been discussed \([39, 40, 41]\). Powders of the alloys containing Cu are more stable on air aging, even as fine particles (Figure 5.19), in comparison with \(\text{Co}_{5}\text{Sm}\) [39]. The liquid - phase sintering technique has been applied to a \(\text{Co}-\text{Cu}-\text{Fe}-\text{Ce}\) alloy by R. C. Sherwood and his associates [42]. Figure 5.20 shows the demagnetizing behavior of a liquid phase sintered \(\text{Co}_{0.8}\text{Cu}_{0.5}\text{Fe}_{0.6}\text{Ce}\) magnet. \((BH)_{max}\) was 9.3\text{ MG - Oe}\), which is approximately equal to that obtained for the cast alloy. \(\text{Co}-\text{Cu}-\text{Fe}-\text{Ce}\) powder magnets with \((BH)_{max}\) of the order of 12\text{ MG - Oe}\) have also been prepared without additives [43]. A method of stabilizing pyrophoric metal powders by coating with a polymer film has been described \([44, 45]\). Continuous hot pressing of \(\text{Co}_{5}\text{Sm}\) powder has recently been discussed [47].

Recapitulation: Summary and Future Perspectives on Co₅R Powder-Based Magnets

The result of the experiments described above is that practical sintering techniques have evolved which can produce permanent magnets having maximum energy products of \(15 - 20\times10^{6}\text{ G - Oe}\). General laboratory procedures are as follows:

(l)(a) An induction or arc melt in an argon atmosphere is made of the base composition, which is usually \(\text{Co}_{5}\text{Sm}\). In addition, a separate melt of the low melting

position (60 wt % Sm + 40 wt % Co) is made. (b) An alternative method requires only a single melt of 63 wt % Co + 37 wt % Sm to be made.

(2) The melts are broken into small pieces and ground into fine powder of about 5 - 20 \(\mu\text{m}\) in \(N_{2}\), toluene, or isopropyl alcohol. An attritor, vibratory, or ball mill is satisfactory for this purpose.

(3) For the method in 1(a), the two compositions are mixed together in such a proportion that the blended powder has the composition 63 wt % Co, 37 wt % Sm. (The powder for the method in 1(b) requires no blending, since it has the preferred composition.)

(4) The powder from step (3) is packed into rubber bags 1/4 to 1/2 in. in diam by 1 1/2 in. long and placed in an axial magnetic field. Values of field as high as 100,000 Oe have been used, but good results have been obtained with fields as low as 15,000 Oe. In this instance, the rubber tube is flexed by hand to aid alignment. The sample is then pressed hydrostatically with 25,000 to 200,000 lb/in.2.

Essentially the same results can be obtained by aligning the powders in a magnetic field in a nonmagnetic die to which pressure is applied.

(5) Finally, the samples are sintered in a purified argon atmosphere at temperatures near \(1125^{\circ}\text{C}\) for approximately 1/2 hr. Temperatures have to be carefully controlled within \(5-10^{\circ}\text{C}\)

The procedures outlined in steps (1) to (5) will yield good - quality permanent magnets. The reader should note, however, that each experimenter may obtain somewhat different results because of variations in the composition of the raw materials and because of the sensitivity of the final magnetic properties to small changes in the processing. Optimization of the different steps will then be necessary and can best be achieved through experience.