Rare Earth Elements and Their Alloys with Cobalt, Copper, and Iron: Properties and Applications

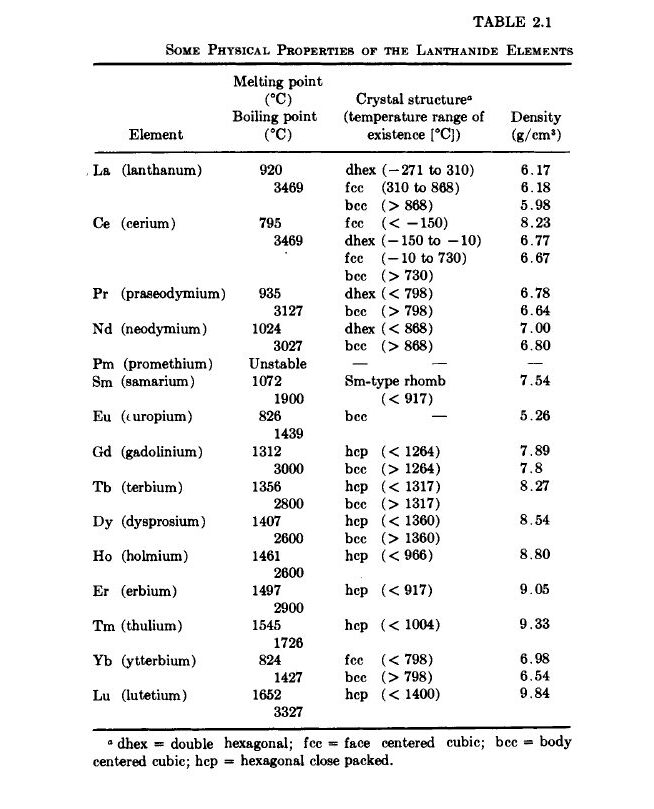

The term rare earth is usually applied to those elements having atomic numbers 58 (Ce) to 71 (Lu) (Table 2.1). Occasionally, the Group 3B elements Sc (21), Y (39), and La (57) are included in this group because they are chemically related to the rare earths. The above terminology, which originated well over 150 years ago, is unfortunate. These metallic elements are not rare in nature; they are now commercially available, are being used in many industrial applications, and will certainly find even wider application in the future as our technology expands. Some of the already established uses are as follows: as ions in laser materials, ferri -

magnetic insulators, and luminescent materials; as a constituent in some glass glazes and protective coatings; and as deoxidizing elements in iron and steel making practice. The latter two uses are a consequence of their large chemical affinity for nonmetallic elements such as oxygen and nitrogen. A new, potentially important use for the rare earth elements is in metallic permanent magnets. This is the subject to be discussed in this monograph.

The Electronic Nature of Rare Earth Elements: Understanding Their Magnetic Behavior

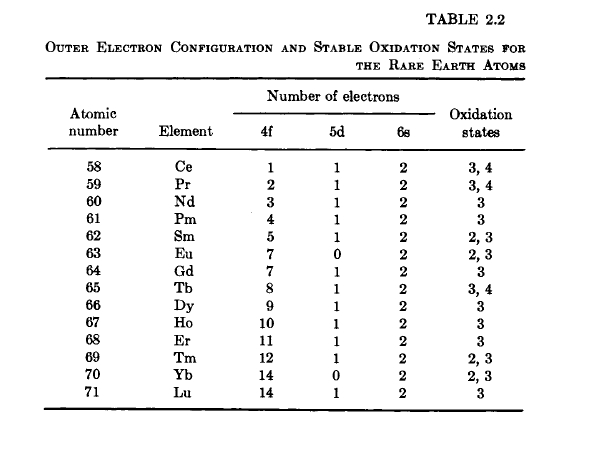

The ground - state outer electronic configuration for the rare earth elements is written as \([\text{Xe}]4f^{n}5d^{m}6s^{2}\), where \([\text{Xe}]\) refers

to the full - shell xenon core. The occupation of the f, d, and s orbitals with increasing atomic number is shown in Table 2.2. The 4f electrons are inner - orbit electrons, i.e., the quantum - mechanical probability distribution function reaches a maximum closer to the nucleus than the d and s electrons. The 5d and 6s electrons are those that partake in bonding. The stable oxidation states or valence states are also shown in Table 2.2.

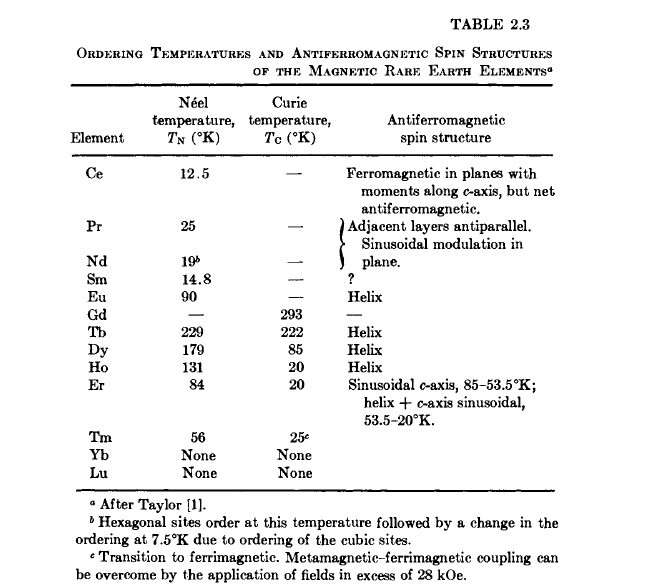

The magnetic behavior of the rare - earth elements is almost entirely due to the unpaired 4f electrons. The magnetic moment is based on the net angular momentum \(J\), which arises from the total spin angular momenta \(S\) of the unpaired 4f electrons and their orbital angular momenta \(L\). When the 4f shell is full, i.e., when all electrons are paired, as is the case for Lu metal, diamagnetic behavior results. Because the net moment is localized about the atom core, these materials are very useful for scientific studies directed toward understanding magnetic phenomena and crystal - field effects. Table 2.3 contains a tabulation of magnetic data of the rare - earth elements [1 - 7]. Gadolinium, whose magnetic moment is due essentially to electron spins only, is ferromagnetic and exhibits the highest Curie temperature (\(T_{C}=293^{\circ}\text{K}\) and observed effective moment \( = 7.94\ \mu_{B}/\text{atom}\)). The heavier rare - earth metals, i.e., those having 4f shells more than half - filled, exhibit both ferromagnetic and antiferromagnetic behavior, and some have rather large effective moments at low temperatures (\(\text{Tb}=9.7\ \mu_{B}/\text{atom}\); \(\text{Dy}=10.6\); \(\text{Ho}=10.4\); \(\text{Er}=9.5\); \(\text{Tm}=7.3\)). They are ferromagnetic at low temperature, antiferromagnetic above \(T_{C}\), and exhibit complex magnetic structures and magnetization behavior. Yb metal is divalent, effectively having a full 4f shell, and does not order magnetically.

Most of the rare - earth atoms are trivalent in the metallic state. The valence electrons (5d and 6s) become conduction

electrons in the metals. The experimental atomic moments of the metals are generally the same as those obtained on the basis of a simple ionic treatment using Hund's rules,* which

* Hund's rules state: (1) Maximum value of spin \(S\) as allowed by the Pauli exclusion principle. (2) Maximum value of orbital angular momentum \(L\) consistent with (1). (3) The value of total angular momentum \(J\) is equal to \((L - S)\) when the shell is less than half - full and to \((L + S)\) when the shell is more than half - full.determine the most stable spin and orbital state of the electron.

The effective magnetic moment of an ion in Bohr magnetons (\(\mu_{B}\)) is \[p_{eff}=g[J(J + 1)]^{1/2}\] where \(J\) is the angular - momentum quantum number. The \(g\) factor or spectroscopic splitting factor is related to the orbital angular momentum \(L\) and spin angular momentum \(S\) by the Landé equation \[g = 1+\frac{J(J + 1)+S(S + 1)-L(L + 1)}{2J(J + 1)}\]

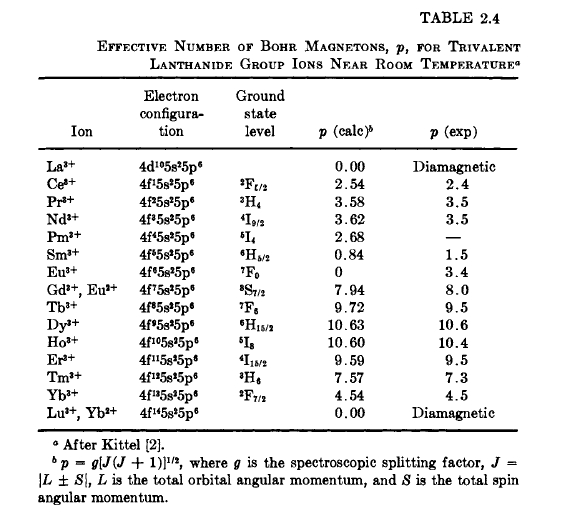

In Table 2.4 are listed the calculated effective moments for the ions in their ground states and the values obtained from measurements of a number of salts in the paramagnetic state. In computing the moments the \(g\) values were obtained from the above equation. \(\text{Gd}^{3 + }\) and \(\text{Eu}^{2+}\) are spin - only ions, i.e., \(J = |S|\). A marked discrepancy between calculated and observed moments exists for \(\text{Eu}^{3+}\) and \(\text{Sm}^{3+}\) ions. This is due to excited states of these ions having energy separations above the ground state comparable to \(kT\). These excited states give rise to a measurable susceptibility. The agreement between the theoretical and experimental values in Table 2.4 indicates that the total moment is localized about the ion.

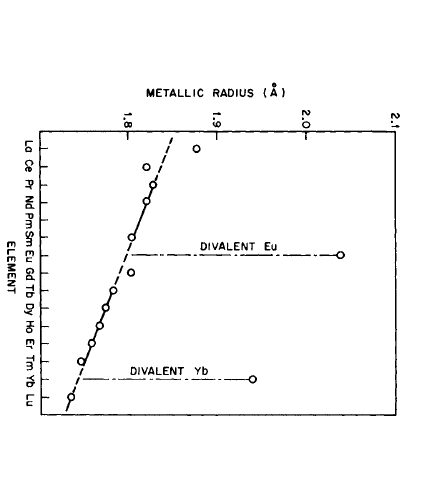

Since half or full 4f shell configurations are quite stable (Hund's rule), \(\text{Eu}(4f^{7}5d^{0}6s^{2})\) and \(\text{Yb}(4f^{14}5d^{0}6s^{2})\) are divalent metals and behave divalently in many metallic alloys and intermetallic compounds. For Ce, there is a tendency to lose one 4f electron and thus exhibit tetravalent behavior in metals and nonmetals. The increase in nuclear charge with increasing atomic number gives rise to the lanthanide contraction* (Figure 2.1).

* The lanthanide contraction refers to the decrease in atomic

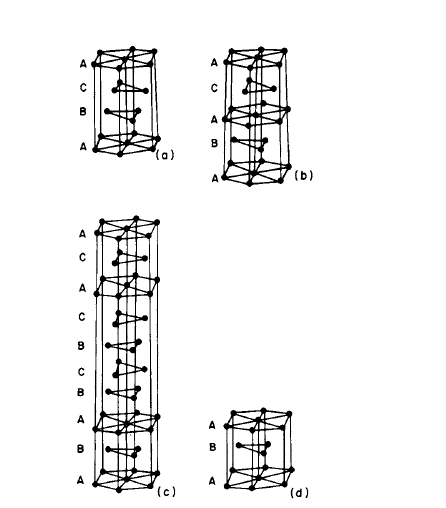

The room - temperature crystal structures (Table 2.1) can be discussed in terms of the stacking of three types of layer, A, B, and C (Figure 2.2). The double - hexagonal structure exists at the lower temperatures and is confined to the light rare - earth elements. Eu and Yb exhibit cubic structures.

or ionic size of the rare - earth atom or ion with increasing atomic number. It is due to the increase in nuclear charge, resulting in greater attraction of the outer electrons to the nucleus.

Figure 2.1 The metallic radii of the rare earth elements, illustrating the lanthanide contraction (after Taylor [1]).

Figure 2.2 The crystal structures of the rare earth elements in terms of three basic layers: (a) face centered cubic (fee), viewed in the (111) direction; (b) double hexagonal (dhex); (c) samarium type; (d) hexagonal close packed. (After Taylor [1].)

Rare Earth Alloys: Composition, Structure, and Technological Uses

The large magnetic moments exhibited by some of the rare - earth elements at low temperatures is essentially the reason for the study of alloys made from rare - earth and 3d - transition metals.

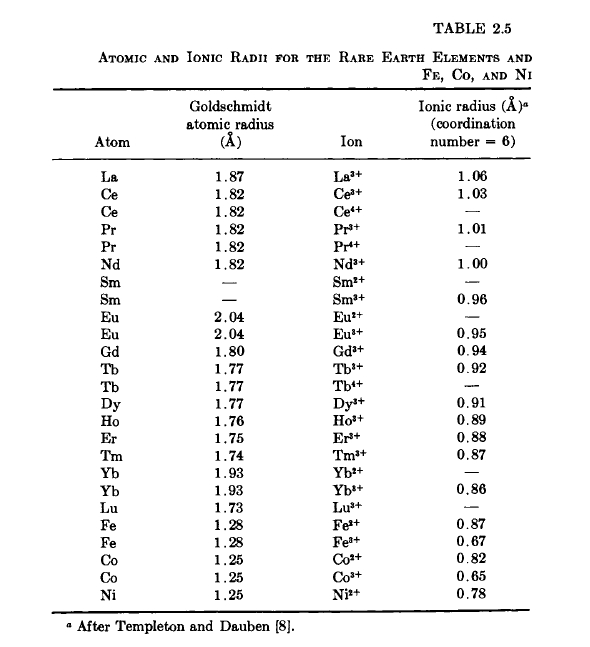

Because of the large difference in atomic radii between rare - earth (R) and Mn, Fe, Co, and Ni atoms (Table 2.5), very little terminal solid solubility exists in rare - earth - 3d - transition element systems. Thus, the probability of forming new ductile magnetic alloys is small and one must study intermetallic compounds in the search for practical materials. A characteristic feature, then, of the binary systems of the rare - earth and 3d - transition elements is the existence of a number of intermetallic compounds. The number of com - pounds tends to increase with increase in the atomic number of the rare - earth atom (decreasing radius of the rare - earth atom); for a given rare - earth, the number of compounds tends to increase with the number of 3d electrons of the alloying element. The relative size of the constituent atoms in rare - earth alloy systems appears to be the primary factor in determining the formation and stability of intermediate phases.

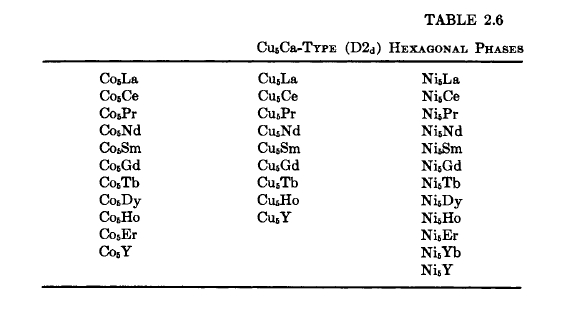

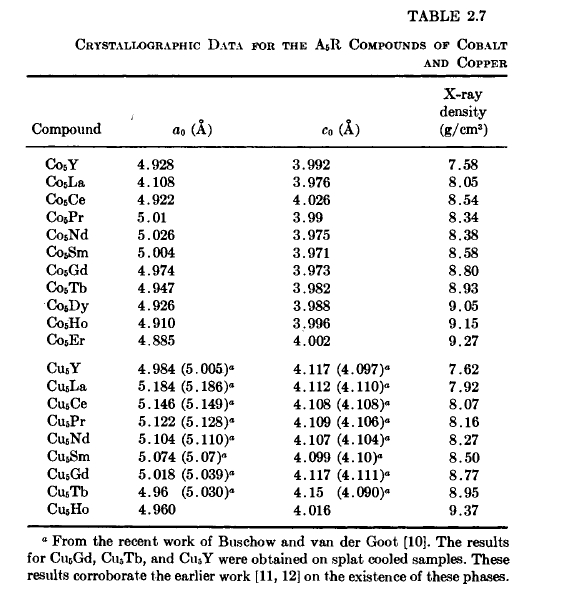

Of particular interest for use as permanent - magnet materials are those rare - earth Co and Cu hexagonal phases having the \(\text{Cu}_{5}\text{Ca}\) structure (\(\text{D}2_{d}\)) (Figure 2.3, Tables 2.6 and 2.7) [11 - 13]. The \(\text{Cu}_{5}\text{R}\) phases are included because they are

Figure 2.3 The \(\text{Cu}_{5}\text{Ca}\) and \(\text{Co}_{17}\text{R}_{2}\) structures (the \(\text{Co}_{17}\text{R}_{2}\) figure is from Bouchet et al. [9]).

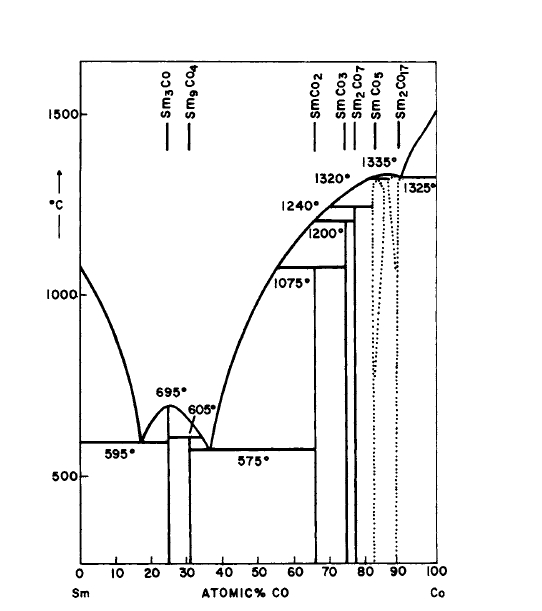

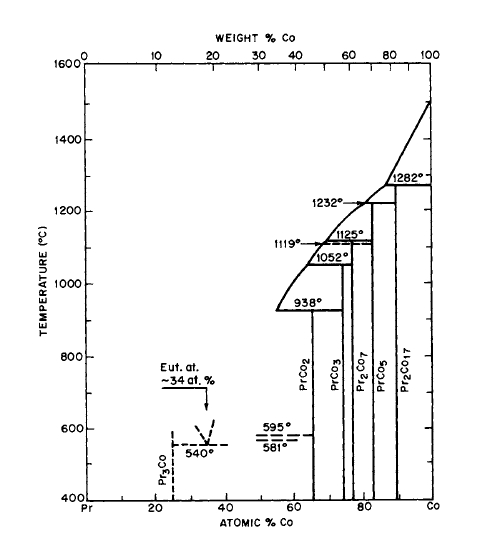

important in the formation of permanent - magnet alloys to be discussed in subsequent sections. The published phase diagrams for the systems pertinent to this monograph are shown in Figures 2.4 through 2.21.*

* The phase diagram for the \(\text{Sm}-\text{Cu}\) system is not known at this time, but it is likely to bear some resemblance to the known \(\text{R}-\text{Cu}\) diagrams.

The \(\text{Cu}_{5}\text{Ca}\) structure, shown in Figure 2.3, contains one formula unit per cell. The R atom is at 000; two Cu or two Co atoms at \(\frac{1}{3}\frac{2}{3}0\); \(\frac{2}{3}\frac{1}{3}0\); and three Cu or three Co atoms at \(\frac{1}{2}0\frac{1}{2}\), \(0\frac{1}{2}\frac{1}{2}\), and \(\frac{1}{2}\frac{1}{2}0\). The Co or Cu atoms occupy two sets of nonequivalent sites. The Laves phases (C14, hexagonal, \(\text{MgZn}_{2}\) type, and C15, cubic, \(\text{MgCu}_{2}\) type) and phases of stoichiometry \(\text{A}_{17}\text{R}_{2}\) also generally form in R - 3d - transition

Figure 2.4 Phase diagram for the Sm-Co system (after Buschow and van der Goot [14]).

![Phase diagram for the Sm Fe system (after Buschow [15]).](https://permanentmagnet.net/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/Phase-diagram-for-the-Sm-Fe-system-after-Buschow-15.jpg)

Figure 2.5 Phase diagram for the Sm - Fe system (after Buschow [15]).

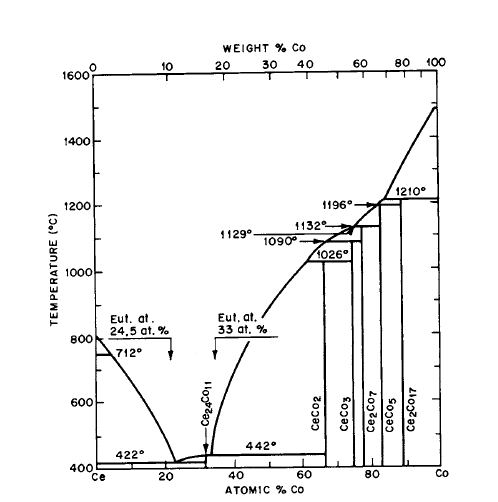

Figure 2.6 Phase diagram for the Pr-Co system (after Ray and Hotter [16]).

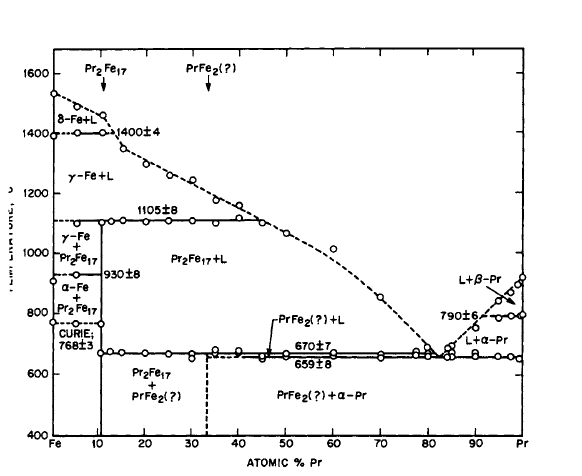

Figure 2.7 Phase diagram for the Pr-Fe system (after Ray and Hoffer [16, 17]).

Figure 2.8 Phase diagram for the Pr - Cu system. PrCu5 is not shown in this version of the diagram. (From "Constitution of Binary Alloys," 1st Suppl., by R. P. Elliot. Copyright 1965, McGraw - Hill. Used with permission of McGraw - Hill Book Company.)

Figure 2.9 Phase diagram for the Ce-Co system (after Ellinger et al [18] and Ray and HofFer [16, 17]).

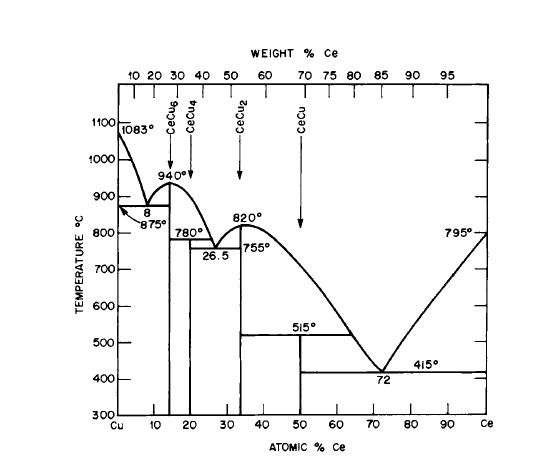

Figure 2.10 Phase diagram for the Ce - Cu system. CeCu5 is not shown in this version of the diagram. (From "Constitution of Binary Alloys," by M. Hansen and K. Anderko. Copyright 1958, McGraw - Hill. Used with permission of McGraw - Hill Book Company.)

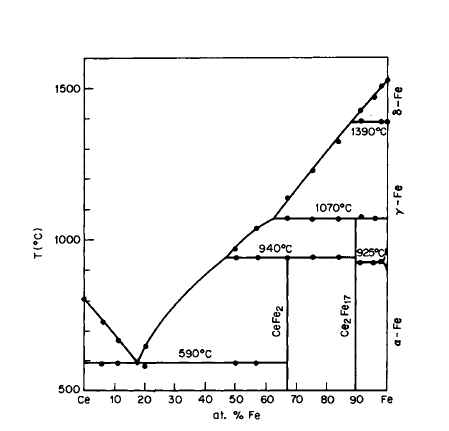

Figure 2.11 Phase diagram for the Ce - Fe system (after Buschow and van Wieringen [21]).

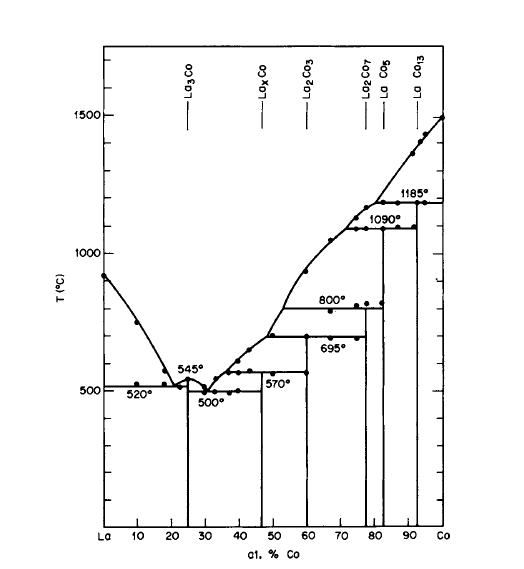

Figure 2.12 Phase diagram for the La - Co system (after Buschow and Velge [22]).

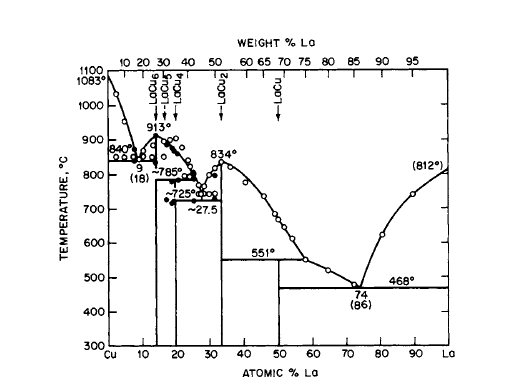

Figure 2.13 Phase diagram for the La - Cu system [7].The existence of LaCu5 is shown on this diagram, but the manner in which it forms is unknown.

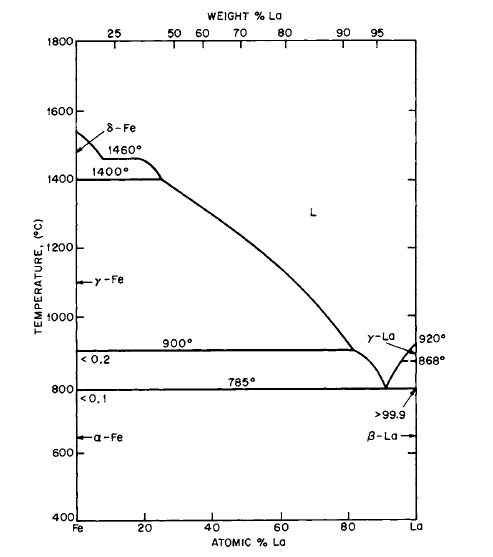

Figure 2.14 Phase diagram for the La-Fe system. (From "Constitution of Binary Alloys," 1st Suppl., by R. P. Elliot. Copyright 1965, McGraw-Hill. Used with permission of McGraw-Hill Book Company.)

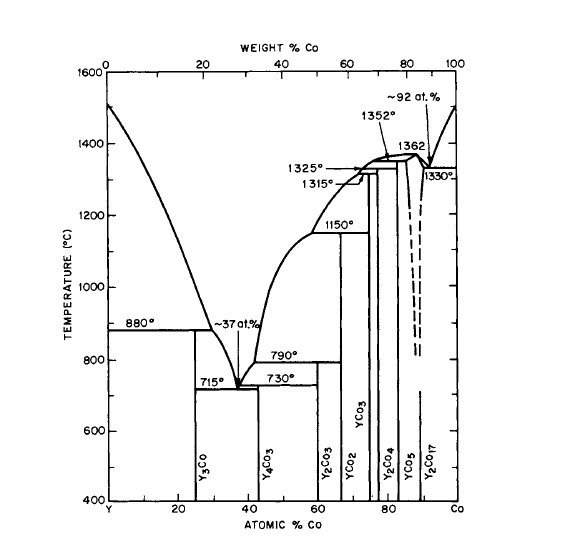

Figure 2.15 Phase diagram for the Y-Co system (after Ray Hoffer [17]).

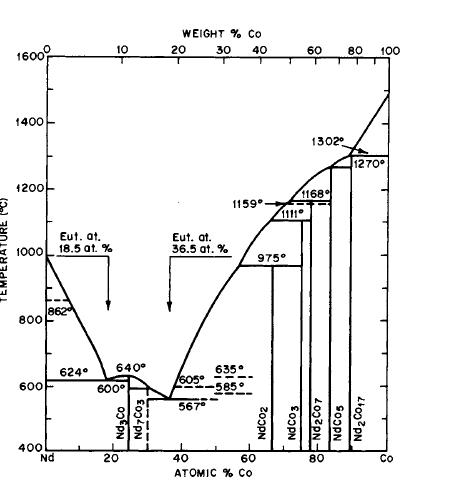

Figure 2.16 Phase diagram for the Nd-Co system (after Ray and Hoffer [16]).

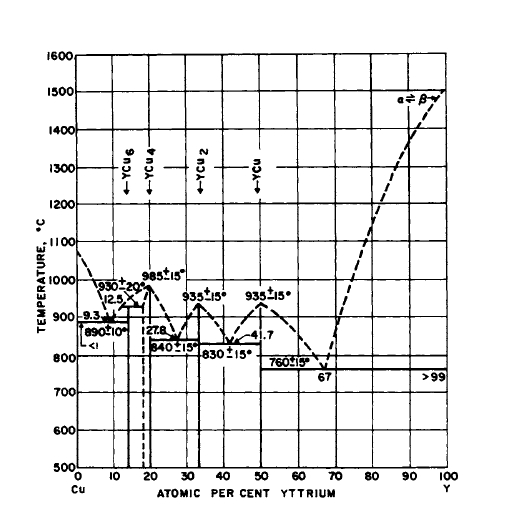

Figure 2.17 Phase diagram for the Y-Cu system. YCu5 is not shown in this version of the diagram. (From "Constitution of Binary Alloys," 1st Suppl., by R. P. Elliot. Copyright 1965, McGraw-Hill. Used with permission of McGraw-Hill Book Company.)

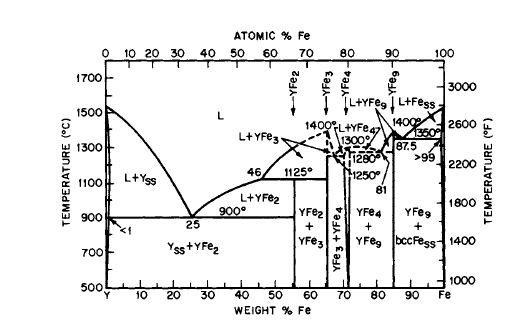

Figure 2.18 Phase diagram for the Y-Fe system (after Domagala et al. [24]).

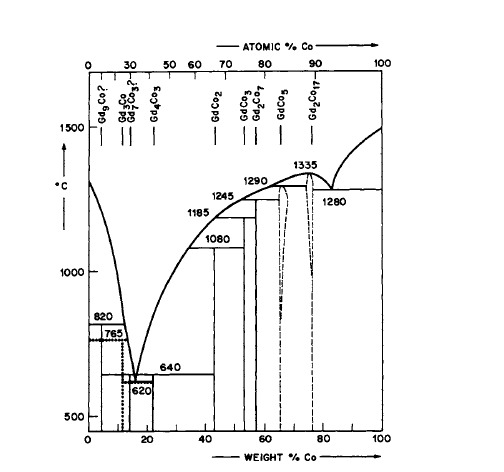

Figure 2.19 Phase diagram for the Gd - Co system (as given by Lihl [25]).

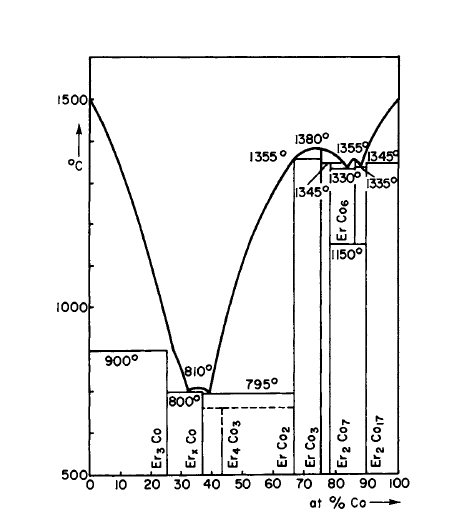

Figure 2.2 Phase diagram for the Er-Co system (after Buschow [26, 54, 55]).

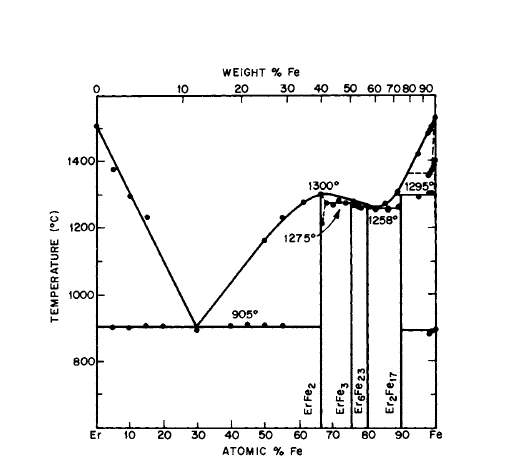

Figure 2.21 Phase diagram for the Er-Fe system (after Meyer [20] and Buschow and van der Goot [27]).

metal systems. The hexagonal \(\text{Cu}_{5}\text{Ca}\) - type structure is related structurally to these phases, as well as to others that form in these systems. For example, in the Co - Sm system (Figure 2.4), in addition to \(\text{Co}_{5}\text{Sm}\), \(\text{Co}_{17}\text{Sm}_{2}\) (\(\text{Zn}_{17}\text{Th}_{2}\) type), and \(\text{Co}_{2}\text{Sm}\) (\(\text{MgCu}_{2}\) type), the phases \(\text{Co}_{3}\text{Sm}\) (\(\text{PuNi}_{3}\) type, rhombohedral), and \(\text{Co}_{7}\text{Sm}_{2}\) (\(\text{Ni}_{7}\text{Ce}_{2}\) type, hexagonal) are also present and are structurally related to the \(\text{Cu}_{5}\text{Ca}\) type.

\(\text{Co}_{5}\text{R}\) and \(\text{Cu}_{5}\text{R}\) Phases: Magnetic and Structural Properties

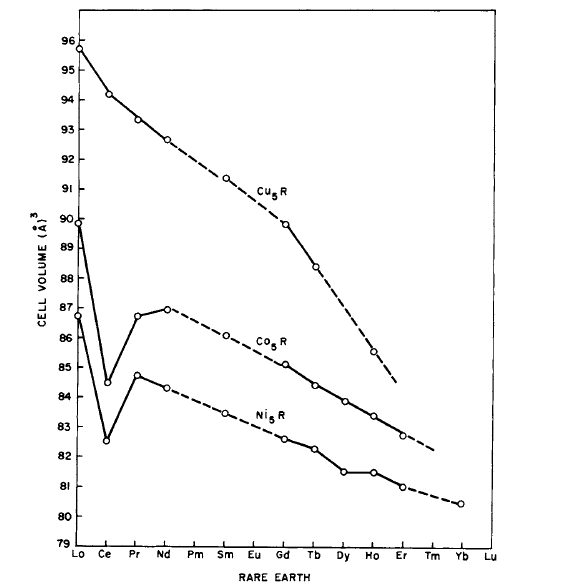

Crystallographic data for the \(\text{Co}_{5}\text{R}\) and \(\text{Cu}_{5}\text{R}\) phases are given in Table 2.7. The variation of cell volume with atomic number of the rare - earth atom is shown in Figure 2.22. The cell volume decreases with increasing atomic number because of the lanthanide contraction. The different behavior of Ce is attributed to the loss of its one 4f electron to the conduction band, resulting in a nearly tetravalent ion. This also appears to occur to some extent for Pr in \(\text{PrCo}_{5}\). The other rare - earth elements behave trivalently. Although Yb is divalent in Yb metal, it is trivalent in \(\text{Ni}_{5}\text{Yb}\) and \(\text{Ni}_{2}\text{Yb}\) (\(\text{MgCu}_{2}\) structure). This information is based on lattice constant data. The trivalent behavior of Yb in the Ni compound is attributed to the ease with which the 3d orbitals can be filled in order to form a closed shell. \(\text{Co}_{5}\text{Eu}\) and \(\text{Co}_{5}\text{Yb}\) do not exist.

The early published Pr - Cu and Ce - Cu phase diagrams (Figures 2.8 and 2.10) contain the \(\text{Cu}_{4}\text{Ce}\) (orthorhombic), \(\text{Cu}_{4}\text{Pr}\), \(\text{Cu}_{6}\text{Ce}\), and \(\text{Cu}_{6}\text{Pr}\) phases but do not show the existence of the \(\text{Cu}_{5}\text{Ce}\) and \(\text{Cu}_{5}\text{Pr}\) phases. Some of the \(\text{Cu}_{5}\text{R}\) phases [11, 12] (\(R = \text{Gd}, \text{Tb}, \text{Dy}, \text{Ho}, \text{Er}, \text{Tm}\)) can also exhibit the cubic \(\text{AuBe}_{5}\) structure [28]. The \(\text{Cu}_{6}\text{R}\) phases, where \(R=\text{Pr}, \text{Nd}, \text{Sm}, \text{Gd}\), are isostructural to the ortho -

Figure 2.22 Variation of cell volume with atomic number of the rare - earth for the \(\text{A}_{5}\text{R}\) phases.

rhombic \(\text{Cu}_{6}\text{Ce}\) structure [29]. The \(\text{Cu}_{6}\text{Ce}\) structure closely resembles the \(\text{Cu}_{5}\text{Ca}\) type [30]. \(\text{Cu}_{6}\text{Tb}\), having the \(\text{Cu}_{6}\text{Ce}\) structure, was obtained only after annealing splat - cooled samples in vacuum at \(700^{\circ}\text{C}\) for four days. However, the samples showed the hexagonal \(\text{Cu}_{5}\text{Ca}\) structure prior to an -

nealing. Such drastic cooling is not necessary to observe the \(\text{Cu}_{5}\text{Ca}\) structure. Crucible melting yields this structure [11, 12]. It is suggested that the hexagonal \(\text{Cu}_{5}\text{Ca}\) phase is either metastable or is a phase occurring only at high temperatures because \(\text{Cu}_{5}\text{Tb}\) exhibits the cubic \(\text{AuBe}_{5}\) structure also [29]. It appears that small deviations in composition affect the stability of the structurally related \(\text{Cu}_{5}\text{R}\) and \(\text{Cu}_{6}\text{R}\) phases.

The range of composition in a given binary system over which the above structures exist have been studied to some extent. \(\text{Co}_{5}\text{Sm}\) exhibits a homogeneity range at elevated temperatures, but is stoichiometric at room temperature (Figure 2.4) [14, 31]. Similarly, \(\text{Co}_{5}\text{Y}\) exhibits a homogeneity range (\(\text{Co}_{4.75}\text{Y}-\text{Co}_{5}\text{Y}\)) at elevated temperatures as determined from quenching and annealing experiments [32, 33]. This is also true for \(\text{Co}_{5}\text{Gd}\) [34]. The deviation from stoichiometric composition appears to increase with atomic number. In fact, in the Er - Co system (Figure 2.20) the 5:1 phase appears not to exist. Instead, a compound \(\text{Co}_{6}\text{Er}\) is observed which exhibits a small homogeneity range and is only stable at elevated temperatures [26]. From studies of this and other R - Co systems, \(\text{Co}_{6}\text{Er}\) is viewed as \(\text{Co}_{5}\text{Er}\) in which some of the Er sites are occupied at random by pairs of Co atoms [14, 26, 32, 33]. In ordered substitution of Er atoms on some of the Co sites in \(\text{Co}_{5}\text{Er}\) results in the compound \(\text{Co}_{7}\text{Er}_{2}\) [26, 35].

Because of the similarity in structures between the \(\text{A}_{5}\text{R}\) and \(\text{A}_{17}\text{R}_{2}\) phases, some studies have been made of the extent of solid solubility of these phases. For the \(\text{Co}_{5}\text{Y}-\text{Co}_{17}\text{Y}_{2}\) and \(\text{Co}_{5}\text{Er}-\text{Co}_{17}\text{Er}_{2}\) systems, measurable solid solubilities do occur.

* It has been shown recently that all of the \(\text{Co}_{5}\text{R}\) phases decompose eutectoidally [56, 57]. The kinetics, however, are sluggish at ordinary temperatures. For \(\text{Co}_{5}\text{Ce}\), \(\text{Co}_{5}\text{Pr}\), and \(\text{Co}_{5}\text{Sm}\), the eutectoid temperatures are approximately \(600^{\circ}\text{C}\), \(600^{\circ}\text{C}\), and \(750^{\circ}\text{C}\) respectively.[32, 33]. This latter result is of importance in our later discussion of the permanent - magnet materials having stoichiometries in excess of 5:1.

\(\text{Fe}_{5}\text{R}\) Phases: Understanding Iron-Based Rare Earth Compounds

The R - Fe phase diagrams shown in Figures 2.5, 2.7, 2.11, 2.14, 2.18, and 2.21 do not show the existence of \(\text{Fe}_{5}\text{R}\) phases, although \(\text{Fe}_{5}\text{Y}\), \(\text{Fe}_{5}\text{Ce}\), \(\text{Fe}_{5}\text{Sm}\), and \(\text{Fe}_{5}\text{Gd}\) having the \(\text{CaCu}_{5}\) structure were reported in the early 1960s [36]. It appears that the above phases of 5:1 stoichiometry do not exist, but \(\text{Fe}_{4}\text{Y}\) does have the \(\text{Cu}_{5}\text{Ca}\) structure, and it is likely that the reported \(\text{Fe}_{5}\text{Y}\) phase was actually \(\text{Fe}_{4}\text{Y}\) [7]. Fe can replace Co in \(\text{Co}_{5}\text{Y}\) to the extent of \(\text{Co}_{4}\text{FeY}\) and still be single - phase. The \(c/a\) ratio changes drastically with Fe content; \(c\) increases and \(a\) decreases rapidly [53].

Multicomponent \(\text{A}_{5}\text{B}\) Phases: Complex Magnetic Alloys and Their Functions

Until the discovery of the cast permanent - magnet alloys in the Co - Cu - Ce and Co - Cu - Sm systems [37], comparatively little research was performed on the \(\text{A}_{5}\text{B}\) systems containing a third element, such as copper. It was shown that large amounts of Cu can be substituted for Co in solid solution in \(\text{Co}_{5}\text{Dy}\) and \(\text{Co}_{5}\text{Tb}\), resulting in substantial changes in magnetic properties and compensation points [38]. No suitable permanent - magnet properties were found in these systems. Similarly, complete solid solubility exists in the \(\text{Ni}_{5}\text{Y}-\text{Cu}_{5}\text{Y}\) and \(\text{Ni}_{5}\text{La}-\text{Ni}_{5}\text{Gd}\) systems [39]. In contrast, the permanent - magnet alloys in

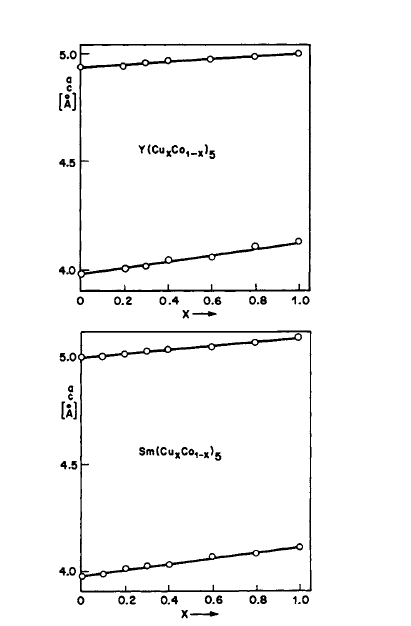

Figure 2.23 Lattice constants as a function of composition in \(\text{Co}_{5}\text{Y}-\text{Cu}_{5}\text{Y}\) and \(\text{Co}_{5}\text{Sm}-\text{Cu}_{5}\text{Sm}\) systems (after Lihl [25]).

the Co - Cu - Ce, Co - Cu - Sm, Co - Cu - Fe - Ce, Co - Cu - Fe - Sm, and Co - Cu - Fe - Ce - Sm systems are multiphase at room temperature under normal conditions. This multiphase structure is highly necessary for the production of practical bulk permanent magnets [37, 40 - 43]. In addition, the alloys are heat treatable, i.e., solution and aging treatments can be performed, resulting in pronounced changes in magnetic properties [37, 40 - 43]. These processes will be discussed in greater detail in subsequent chapters. Recently, it has been reported that spinodal decomposition occurs in the \(\text{Co}_{5 - x}\text{Cu}_{x}\text{Sm}\) system for \(x = 1.5\) and 2, and that quenched alloys in \(\text{Co}_{5}\text{Y}-\text{Cu}_{5}\text{Y}\) and \(\text{Co}_{5}\text{Sm}-\text{Cu}_{5}\text{Sm}\) systems show complete solid solubility at elevated temperatures [25, 44]. The variation of the lattice constants at room temperature for the \(\text{Co}_{5}\text{Y}-\text{Cu}_{5}\text{Y}\) and \(\text{Co}_{5}\text{Sm}-\text{Cu}_{5}\text{Sm}\) systems is shown in Figure 2.23. These results are not inconsistent with the results of the earlier work [37, 40 - 43] regarding the heat treatability of these materials.

Phases of Stoichiometry \(\text{A}_{17}\text{R}_{2}\) Structure, Stability, and Applications

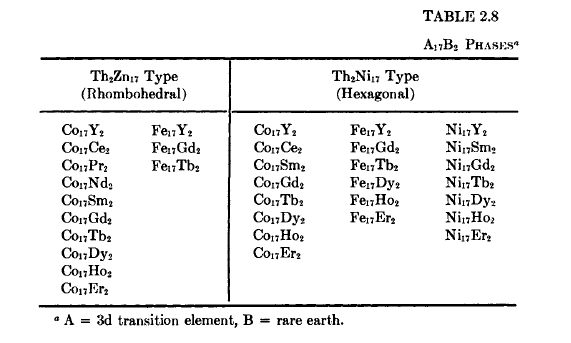

As noted earlier, phases of stoichiometry \(\text{A}_{17}\text{B}_{2}\) (Table 2.8 [13, 45 - 50]), where \(A=\text{Co}, \text{Fe}, \text{Ni}\), are closely related to the \(\text{Cu}_{5}\text{Ca}\) structure. They either have the \(\text{Ni}_{17}\text{Th}_{2}\) (hexagonal) or \(\text{Zn}_{17}\text{Th}_{2}\) (rhombohedral) structures (Figure 2.3). The close structural relation between the \(\text{Cu}_{5}\text{Ca}\) and \(\text{A}_{17}\text{R}_{2}\) structures can be seen by examining Figure 2.3. It will be noted that the \(\text{Ni}_{17}\text{Th}_{2}\) and \(\text{Zn}_{17}\text{Th}_{2}\) phases have \(\text{Cu}_{5}\text{Ca}\) - like subcells and differ only in the stacking of these subcells. These phases can be derived from the \(\text{Co}_{5}\text{R}\) phases by replacing one - third of the rare - earth atoms with pairs of smaller Co atoms

[51]. The actual structure assumed tends to depend on the size of the R atom. The \(\text{Zn}_{17}\text{Th}_{2}\) structure appears to be preferred by the light R elements whereas the \(\text{Ni}_{17}\text{Th}_{2}\) structure is preferred by the heavier R elements, although the cooling rate after preparation and/or the existence of homogeneity ranges at elevated temperature are important because some can exist at room temperature in both forms [9].

Although \(\text{Fe}_{17}\text{R}\) phases isostructural to the 17:2 phases have been reported (perhaps suggesting a homogeneity range for the corresponding \(\text{A}_{17}\text{B}_{2}\) [\(\text{A}_{8.5}\text{B}\)] phases), recent studies [45] show no evidence for the existence of a distinct phase of stoichiometry \(\text{Fe}_{7}\text{Pr}\) and suggest that this is true for \(\text{Fe}_{7}\text{Ce}\), \(\text{Fe}_{7}\text{Nd}\), \(\text{Fe}_{7}\text{Sm}\), and \(\text{Fe}_{7}\text{Gd}\).

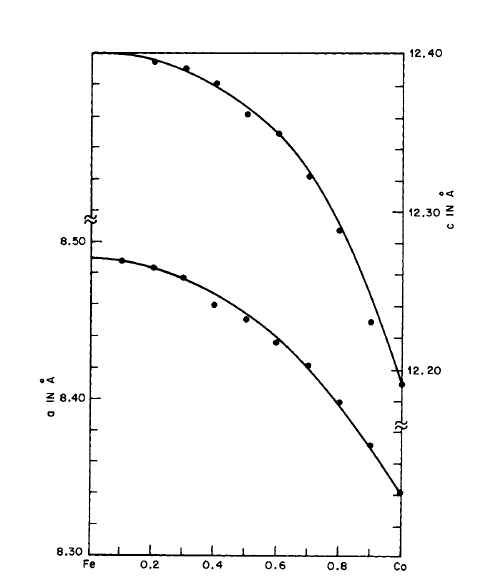

The magnetic properties of the \(\text{Co}_{17}\text{R}_{2}\) phases can be varied by forming solid solutions with \(\text{Fe}_{17}\text{R}_{2}\) phases (Chapter III). Lihl [25] has shown, for example, that a complete series of solid solutions can be formed in the \(\text{Co}_{17}\text{Y}_{2}-\text{Fe}_{17}\text{Y}_{2}\) system (Figure 2.24).

Figure 2.24 Lattice constants as a function of composition in the \(\text{Co}_{17}\text{Y}_{2}-\text{Fe}_{17}\text{Y}_{2}\) system (after Lihl [25]).

Preparation of Rare Earth Alloys: Methods and Techniques

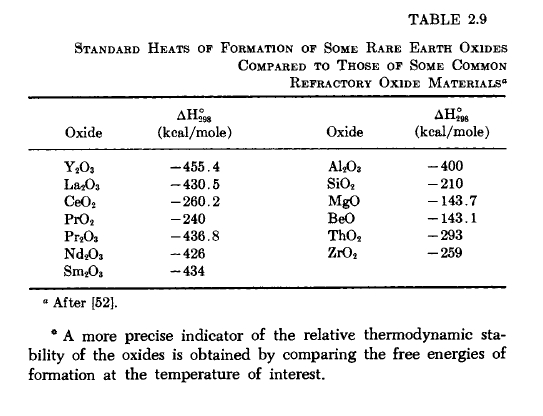

As indicated earlier, the rare - earth elements are quite reactive, i.e., the oxides of these elements exhibit large negative heats of formation and consequently react to some extent with the common oxide refractories (Table 2.9).* \(\text{Y}_{2}\text{O}_{3}\) appears to be a good candidate for a refractory material. Nevertheless, the early structural and magnetic studies of \(\text{A}_{5}\text{B}\) phases were carried out on samples prepared by direct coupling induction melting in recrystallized (high density) \(\text{Al}_{2}\text{O}_{3}\) crucibles in an inert atmosphere, usually argon. Small melts for experimental studies are now usually prepared by inert electrode arc melting or silver boat melting. Because preferred crystalline or grain alignment in a given direction is important in exploiting

the large magnetocrystalline anisotropy of \(\text{Co}_{5}\text{R}\) phases in R - Co - Cu - Fe alloys (Chapters IV and V), casting techniques involving refractory materials are being utilized commercially for directional solidification of permanent magnets.

Examination of the available phase diagrams reveals that all \(\text{Co}_{5}\text{R}\) phases form peritectically by reaction of liquid with the congruent \(\text{Co}_{17}\text{R}_{2}\) phase (except in the La - Co system, Figure 2.12), but since the composition of the liquid in equilibrium with solid \(\text{Co}_{17}\text{R}_{2}\) at the peritectic temperature is in most cases very close to \(\text{Co}_{5}\text{R}\), nearly single - phase alloys form directly from the melt. Samples prepared by cold hearth techniques will, of course, be more inhomogeneous, but can be annealed in vacuum or in a purified inert atmosphere for homogenization, if desired.

Of the rare - earth elements of importance for magnets, Sm exhibits the highest vapor pressure at \(1500^{\circ}\text{C}\) (see Table 2.1, boiling point \(1900^{\circ}\text{C}\)) and a small Sm loss occurs during melting.